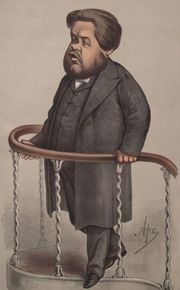

Charles Spurgeon

| Charles Haddon Spurgeon | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 19, 1834 Kelvedon, Essex, England |

| Died | January 31, 1892 (aged 57) Menton, Alpes-Maritimes, France |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Pastor, author |

| Religion | Christian (Reformed Baptist) |

| Spouse | Susannah Spurgeon (née Thompson) (January 8, 1856) |

| Children | Charles & Thomas Spurgeon (twins) (1856) |

| Parents | John & Eliza Spurgeon |

Charles Haddon (C.H.) Spurgeon (June 19, 1834 – January 31, 1892) was a British Particular Baptist preacher who remains highly influential among Christians of different denominations, among whom he is still known as the "Prince of Preachers". This despite the fact that he was a strong figure in the Reformed Baptist tradition, defending the Church in agreement with the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith understanding, against liberalism and pragmatic theological tendencies even in his day.

In his lifetime, Spurgeon preached to around 10,000,000 people,[1] often up to 10 times each week at different places. His sermons have been translated into many languages. Spurgeon was the pastor of the congregation of the New Park Street Chapel (later the Metropolitan Tabernacle) in London for 38 years.[2] He was part of several controversies with the Baptist Union of Great Britain and later had to leave that denomination.[3] In 1857, he started a charity organization called Spurgeon's which now works globally. He also founded Spurgeon's College, which was named after him posthumously.

Spurgeon was a prolific author of many types of works including sermons, an autobiography, a commentary, books on prayer, a devotional, a magazine, poetry,[4] hymnist,[5] and more. Many sermons were transcribed as he spoke and were translated into many languages during his lifetime.

Contents |

Early beginnings

Born in Kelvedon, Essex, Spurgeon's conversion to Christianity came on January 6, 1850, at age fifteen. On his way to a scheduled appointment, a snow storm forced him to cut short his intended journey and to turn into a Primitive Methodist chapel in Colchester where "God opened his heart to the salvation message." The text that moved him was Isaiah 45:22 - "Look unto me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth, for I am God, and there is none else."

Later that year, on April 4, 1850, he was admitted to the church at Newmarket. His baptism followed on May 3 in the river Lark, at Isleham. Later that same year he moved to Cambridge. He preached his first sermon in the winter of 1850-51 in a cottage at Teversham, Cambridge; from the beginning of his ministry his style and ability were considered to be far above average. In the same year, he was installed as pastor of the small Baptist church at Waterbeach, Cambridgeshire, where he published his first literary work: a Gospel tract written in 1853.

New Park Street Chapel

| Part of a series on |

| Baptists |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Protestantism · Puritanism Anabaptism |

| Soteriology |

| General · Strict · Reformed |

| Doctrinal distinctives |

| Priesthood of all believers Individual soul liberty Separation of

Sola scripturachurch and state Congregationalism Ordinances · Offices Confessions |

| Key figures |

| John Smyth Thomas Helwys Roger Williams John Bunyan Shubal Stearns Andrew Fuller Charles Spurgeon D. N. Jackson |

| Conventions and Unions |

In April 1854, after preaching three months on probation and just four years after his conversion, Spurgeon, then only 19, was called to the pastorate of London's famed New Park Street Chapel, Southwark (formerly pastored by the Particular Baptists Benjamin Keach, theologian John Gill, and John Rippon). This was the largest Baptist congregation in London at the time, although it had dwindled in numbers for several years. Spurgeon found friends in London among his fellow pastors, such as William Garrett Lewis of Westbourne Grove Church, an older man who along with Spurgeon went on to found the London Baptist Association. Within a few months of Spurgeon's arrival at Park Street, his ability as a preacher made him famous. The following year the first of his sermons in the "New Park Street Pulpit" was published. Spurgeon's sermons were published in printed form every week and had a high circulation. By the time of his death in 1892, he had preached nearly 3,600 sermons and published forty-nine volumes of commentaries, sayings, anecdotes, illustrations, and devotions.

Immediately following his fame was controversy. The first attack in the Press appeared in the Earthen Vessel in January 1855. His preaching, although not revolutionary in substance, was a plain-spoken and direct appeal to the people, using the Bible to provoke them to consider the claims of Jesus Christ. Critical attacks from the media persisted throughout his life.

The congregation quickly outgrew their building; it moved to Exeter Hall, then to Surrey Music Hall. In these venues Spurgeon frequently preached to audiences numbering more than 10,000. At twenty-two, Spurgeon was the most popular preacher of the day.[6]

On January 8, 1856, Spurgeon married Susannah, daughter of Robert Thompson of Falcon Square, London, by whom he had twin sons, Charles and Thomas born on September 20, 1856. At the end of that year, tragedy struck on October 19, 1856, as Spurgeon was preaching at the Surrey Gardens Music Hall for the first time. Someone in the crowd yelled, "Fire!" The ensuing panic and stampede left several dead. Spurgeon was emotionally devastated by the event and it had a sobering influence on his life. He struggled against depression for many years and spoke of being moved to tears for no reason known to himself.

Walter Thornbury later wrote in "Old and New London" (1897) describing a subsequent meeting at Surrey:

| “ | a congregation consisting of 10,000 souls, streaming into the hall, mounting the galleries, humming, buzzing, and swarming – a mighty hive of bees – eager to secure at first the best places, and, at last, any place at all. After waiting more than half an hour – for if you wish to have a seat you must be there at least that space of time in advance… Mr. Spurgeon ascended his tribune. To the hum, and rush, and trampling of men, succeeded a low, concentrated thrill and murmur of devotion, which seemed to run at once, like an electric current, through the breast of everyone present, and by this magnetic chain the preacher held us fast bound for about two hours. It is not my purpose to give a summary of his discourse. It is enough to say of his voice, that its power and volume are sufficient to reach every one in that vast assembly; of his language that it is neither high-flown nor homely; of his style, that it is at times familiar, at times declamatory, but always happy, and often eloquent; of his doctrine, that neither the 'Calvinist' nor the 'Baptist' appears in the forefront of the battle which is waged by Mr. Spurgeon with relentless animosity, and with Gospel weapons, against irreligion, cant, hypocrisy, pride, and those secret bosom-sins which so easily beset a man in daily life; and to sum up all in a word, it is enough to say, of the man himself, that he impresses you with a perfect conviction of his sincerity. | ” |

Still the work went on. A Pastors' College was founded in 1857 by Spurgeon and was renamed Spurgeon's College in 1923 when it moved to its present building in South Norwood Hill, London;[1]. At the Fast Day, October 7, 1857, he preached to the largest crowd ever – 23,654 people – at The Crystal Palace in London. Spurgeon noted:

| “ | In 1857, a day or two before preaching at the Crystal Palace, I went to decide where the platform should be fixed; and, in order to test the acoustic properties of the building, cried in a loud voice, "Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world." In one of the galleries, a workman, who knew nothing of what was being done, heard the words, and they came like a message from heaven to his soul. He was smitten with conviction on account of sin, put down his tools, went home, and there, after a season of spiritual struggling, found peace and life by beholding the Lamb of God. Years after, he told this story to one who visited him on his death-bed. | ” |

Metropolitan Tabernacle

On March 18, 1861, the congregation moved permanently to the newly constructed purpose-built Metropolitan Tabernacle at Elephant and Castle, Southwark, seating five thousand people with standing room for another one thousand. The Metropolitan Tabernacle was the largest church edifice of its day and can be considered a precursor to the modern "megachurch".[7] Spurgeon continued to preach there several times per week until his death 31 years later. He never gave altar calls at the conclusion of his sermons, but he always extended the invitation that if anyone was moved to seek an interest in Christ by his preaching on a Sunday, they could meet with him at his vestry on Monday morning. Without fail, there was always someone at his door the next day. He wrote his sermons out fully before he preached, but what he carried up to the pulpit was a note card with an outline sketch. Stenographers would take down the sermon as it was delivered; Spurgeon would then have opportunity to make revisions to the transcripts the following day for immediate publication. His weekly sermons, which sold for a penny each, were widely circulated and still remain one of the all-time best selling series of writings published in history.

Besides sermons, Spurgeon also wrote several hymns and published a new collection of worship songs in 1866 called "Our Own Hymn Book". It was mostly a compilation of Isaac Watts' Psalms and Hymns that had been originally selected by John Rippon, a Baptist predecessor to Spurgeon. Singing in the congregation was exclusively a cappella under his pastorate. Thousands heard the preaching and were led in the singing without any amplification of sound that exists today. Hymns were a subject that he took seriously. While Spurgeon was still preaching at New Park Street, a hymn book called "The Rivulet" was published. Spurgeon's first controversy arose because of his critique of its theology, which was largely deistic. At the end of his review, Spurgeon warned:

| “ | We shall soon have to handle truth, not with kid gloves, but with gauntlets, – the gauntlets of holy courage and integrity. Go on, ye warriors of the cross, for the King is at the head of you. | ” |

On June 5, 1862, Spurgeon also challenged the Church of England when he preached against baptismal regeneration.[8] However, Spurgeon taught across denominational lines as well. It was during this period at the new Tabernacle that Spurgeon found a friend in James Hudson Taylor, the founder of the inter-denominational China Inland Mission. Spurgeon supported the work of the mission financially and directed many missionary candidates to apply for service with Taylor. He also aided in the work of cross-cultural evangelism by promoting "The Wordless Book", a teaching tool that he described in a message given on January 11, 1866, regarding Psalm 51:7: "Wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow." This "book" has been and is still used to teach uncounted thousands of illiterate people – young and old – around the globe about the Gospel message.[9][10]

Following the example of George Müller, Spurgeon founded the Stockwell Orphanage, which opened for boys in 1867 and for girls in 1879, and which continued in London until it was bombed in the Second World War.[2] [3] [4] This orphanage became Spurgeon's Child Care which still exists today.

On the death of missionary David Livingstone in 1873, a discolored and much-used copy of one of Spurgeon's printed sermons, "Accidents, Not Punishments,"[11] was found among his few possessions much later, along with the handwritten comment at the top of the first page: "Very good, D.L." He had carried it with him throughout his travels in Africa. It was returned to Spurgeon and treasured by him.[12]

Downgrade Controversy

A controversy among the Baptists flared in 1887 with Spurgeon's first "Down-grade" article, published in The Sword & the Trowel. In the ensuing "Downgrade Controversy," the Metropolitan Tabernacle became disaffiliated from the Baptist Union, effectuating Spurgeon's congregation as the world's largest self-standing church. Contextually the Downgrade Controversy was British Baptists' equivalent of hermeneutic tensions which were starting to sunder Protestant fellowships in general. The Controversy took its name from Spurgeon's use of the term "Downgrade" to describe certain other Baptists' outlook toward the Bible (i.e., they had "downgraded" the Bible and the principle of sola scriptura). [13] Spurgeon alleged that an incremental creeping of the Graf-Wellhausen hypothesis , Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, and other concepts was weakening the Baptist Union and reciprocally explaining the success of his own evangelistic efforts. In the standoff, which even split his pupils trained at the College, each side accused the other of raising issues which did not need to be raised.[14][15]

Final years and death

Often Spurgeon's wife was too ill to leave home to hear him preach. C.H. Spurgeon too suffered ill health toward the end of his life, afflicted by a combination of rheumatism, gout, and Bright's disease. He often recuperated at Menton, near Nice, France, where he eventually died on 1892 January 31. Spurgeon's wife and sons outlived him. His remains were buried at West Norwood Cemetery in London, where the tomb is still visited by admirers.

Spurgeon near the end of his life. |

The tomb of Charles Haddon Spurgeon |

Library

William Jewell College in Liberty, Missouri purchased Spurgeon's 5,103-volume library collection for £500 ($2500) in 1906. The collection was purchased by Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary [5]in Kansas City, Missouri in 2006 for $400,000 and is currently undergoing restoration. A special collection of Spurgeon's handwritten sermon notes and galley proofs from 1879–1891 resides at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama.[6] Spurgeon's College in London also has a small number of notes and proofs.

Works

|

|

Spurgeon's works have been translated into many languages, including: Arabic, Armenian, Bengali, Bulgarian, Castilian (for the Argentine Republic), Chinese, Kongo, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Estonian, French, Gaelic, German, Hindi, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Kaffir, Karen, Lettish, Maori, Norwegian, Polish, Russian, Serbian, Spanish, Swedish, Syriac, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, and Welsh, with a few sermons in Moon's and Braille type for the blind. He also wrote many volumes of commentaries, sayings, and other types of literature.[16]

References

- ↑ "Charles H. Spurgeon". Bath Road Baptist Church. http://www.iclnet.org/pub/resources/text/history/spurgeon/sp-bio.html. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ↑ "History of the Tabernacle". Metropolitan Tabernacle. http://www.metropolitantabernacle.org/?page=history. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ↑ Farley, William P. "Charles Haddon Spurgeon: The Greatest Victorian Preacher". Enrichment Journal. http://enrichmentjournal.ag.org/200701/200701_136_Spurgeon.cfm. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ↑ Immanuel ,Christian Hymn-writers ed Elsie Houghton,Charles Haddon Spurgeon,Evangelical Press of Wales,Bridgend,Wales 1982 ISBN 0 900898 66 6

- ↑ The Baptist Hymn Book,Psalms and Hymn Trust,London,1982

- ↑

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900. London: Smith, Elder & Co. - ↑ Austin (2007), p.86

- ↑ Baptismal Regeneration

- ↑ The Wordless Book

- ↑ Austin (2007), 1-10

- ↑ "Accidents, Not Punishments"

- ↑ W. Y. Fullerton, Charles Haddon Spurgeon: A Biography, ch. 10

- ↑ "The Down Grade Controversy". reformedreader.org. http://www.reformedreader.org/spurgeon/dgcindex.htm. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ An accessible analysis, sympathetic to Spurgeon but no less useful, of the Downgrade Controversy appears at http://www.tecmalta.org/tft351.htm. Also see Dennis M. Swanson, "The Down Grade Controversy and Evangelical Boundaries," at http://www.narnia3.com/articles/ETS%202001.pdf

- ↑ See, e.g., Jack Sin (2000), "The Judgement Seat of Christ," The Burning Bush 6(2), pp. 302-323, esp. p. 310:"The Burning Bush" (PDF). Far Eastern Bible College,Singapore. July 2000. http://www.febc.edu.sg/assets/pdfs/bbush/The%20Burning%20Bush%20Vol%206%20No%202.pdf.

- ↑ "Spurgeon's Writings". The Spurgeon Archive. http://www.spurgeon.org/spwrtngs.htm. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

Further reading

- Austin, Alvyn (2007). China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- Murray, Iain (1972). The Forgotten Spurgeon. Edinburgh UK: Banner of Truth. ISBN 978-0851511566. http://www.amazon.com/Forgotten-Spurgeon-Iain-H-Murray/dp/0851511562/ref=cm_cr-mr-title.

- C. H. Spurgeon (1995). Tom Carter. ed (Trade Pbk. edition). 2200 Quotations from the Writings of Charles H. Spurgeon. Baker Books. ISBN 978-0801053658. http://www.amazon.com/200-Quotations-Topically-Textually-Scripture/dp/080105365X.

- The Standard Life of C. H. Spurgeon. London: Passmore and Alabaster.

- C H Spurgeon "The People's Preacher". Christian Television Association 2010 (of the UK)

External links

- More information on Charles Spurgeon

- Spurgeon Gems – Over 3,500 of Spurgeon's sermons

- Spurgeon quotes

- Metropolitan Tabernacle official site

- Autobiography of Charles Spurgeon, volume 1

- Autobiography of Charles Spurgeon, volume 2

- Autobiography of Charles Spurgeon, volume 3

- Autobiography of Charles Spurgeon, volume 4

- Charles Haddon Spurgeon, A Biography – By William Young Fullerton

- Traits of Character: Being Twenty-five Years' Literary and Personal Recollections, with a chapter on Spurgeon, by Eliza Rennie

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Walters |

Pastor of the Metropolitan Tabernacle 1854-1892 |

Succeeded by Arthur Tappan Pierson |